Steam

Locomotives of India~ the

complete site on Indian steam

Wankaner

- the last bastion

Photographs

and content - Dileep

Prakash

Worldwide railway systems are retaining

and reviving some of the steam locos. India, however, is still realising the

beauty of steam. India has discontinued, rather dieselised, most of the sections

running on steam in the 1990's. The Indian Railways have recently woken up to

the charm of the steam locomotive. The last bastion of steam was the Wankaner

section of Western Railway.

Steam

had been an integral part of childhood. From Ajmer (one of the biggest steam

loco yards in India) the Mayo Special brought me from school to Delhi four times

a year for 9 years. It was always pulled by a steam engine. I

still remember the coal bits that would wander into my shirt pockets and my

scruffy hair by the end of the 16 hour journey. We used to occasionally

steal a ride on the footboard of the YP watching the fireman stuff coal into

the boiler and the driver pull the whistle. However, as the years passed these

memories of steam gradually ebbed. It was while watching a BBC programme on

India, which showed some excellent footage on steam locomotives, that suddenly

refreshed my childhood experiences of steam. The hisses and the puffs, the whistle

and the chug and of course the bits of coal. That's when I got 'steam fever'.

The

Indian Railways is a very difficult organisation to access information. From

when I started my hunt for steam in India and to the day I finally got to experience

it, it took me almost what it takes a human to produce a baby! Well after having

done all the research I could, I was headed for Wankaner in the Rajkot division

of Western Railway with 8 copies of the permission letter in hand!

After a super-fast over-night journey on the Ashram Express to Ahmedabad I boarded

the Bhopal-Rajkot Express for Rajkot enroute to Wankaner. It was a long 3 hr

journey when I suddenly saw smoke and jumped at the sight of Wankaner. There

they were the last few (16 in all, 9 working) YG and YP class steam locos made

by TELCO in the late 1950's. All waiting to be shot. The

sky was overcast and a strong breeze blowed away the steam and smoke from the

engines filling my nostrils with the age -old aroma of coal and steam.

I

went straight to the drivers' shed. It seemed to be instinctive (from the experience

of school days). There I got the details and future of the steam in Wankaner.

"The rail-bus will be here in a month and the goods operation is going to be

blocked in the next few days" said an old driver. Phew !, I am really lucky

to have made it to the last bastion of steam in India. The Darjeeling and Ooty

trains are the more touristy steams and may not close down so soon. But this

is the last place to have general goods and passenger movement on steam locos.

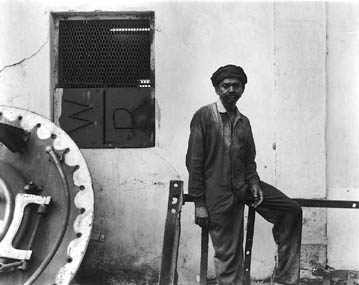

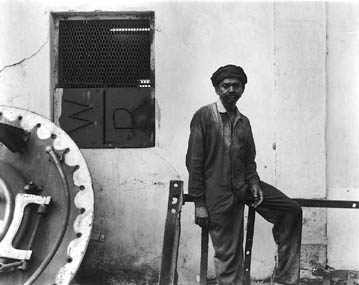

The older staff, the drivers, firemen and linemen swear by steam. They refer

to the engines as 'power'. "This is what earned the money for the Indian Railways.

And you see the emblem of the IR it has a steam loco on it. If you put a diesel

or an electric engine there it will not have any impact or power that the steam

engine has," says Ahmed whose last 3 generations have been drivers for IR.

The

track from Wankaner connects the broad guage main line that runs from Gandhidham.

It goes through Makansar, Rafaleshwar, Morbi (which was, till independence,

the 'Morvi State Railway'), Dahinsara and finally Maliya Miyana at the mouth

of the Little Rann Of Kutch.

The ride to Morbi is quite exciting with the track meandering around the shallow

hills that occasionally crop up along the route. I wait for the 7.15pm loco

to Morbi after shooting the down train from a small hill (the camera almost

got blown off by the 40 kmph wind!) about a kilometre from Rafaleshwar.

The station at Rafaleshwar seems almost as if it is in no man's land. A strong

cool breeze blows coal bits that my hair has collected since the steamy and

smoky morning of documenting steam. And except for the mellowing tweeting of

birds the only other faint sound is of the gatekeeper's radio as he tunes into

some Tamil songs on his radio and seems to enjoy himself. It can get quite lonely

manning a small gate crossing at a place like Rafaleshwar. The lamps to be placed

at the gate still run on kerosene and look quite antique.

The gateman feeds the sparrows, pigeons, and doves that come in droves to peck

and drink water. The railway station is a cool open shed supported by steel

gurders made by 'Dugree' in 1927. The wrought iron benches are also of the same

antiquity. Their wooden planks smoothened by the wind and generations of human

touch. The grey paint on the gurders has cracked and looks like lichens on a

rock. The sleepers below the iron rail have worn into earthy rock looking creatures

and so has the wood of the benches. The feeling is

of a place that has gone through eons of aging and will soon die to be born

as an ugly concretized 'modern' vista of rail civilization. The sweet

whistle of the engine will soon be gone. Probably much before this writing reaches

the press. As the weak sun goes lower into the horizon the distant cries of

a jackal fill the air. The steam 'power' can be heard from a distance as it

is carried in with the wind.

Morbi

is a dirty developing town with hundreds of pigs, autorickshaws and trucks that

move about the town spewing fumes and dust. There is a large temple at Morbi,

which I only saw from the outside. It is by a river very near the railway station.

The railway station is beautiful. The terrace is even better. It seems to have

been built by the Maharaja of Morbi some 200 yrs ago for his private state railway

that operated here. I stayed in the retiring room,

which was huge with old shisham furniture, and a four blade huge fan that moved

as in the good old days at Mayo. Infact that entire first floor of

the station was so much like school. Having got sick of Gujarati food I decided

to try Friend's Food as suggested by the foreign travellers which was not so

good and quite expensive for a budget traveller.

The journey from Morbi to Maliya Miyana is quite disheartening. The entire way

is being broad gauged and there is hordes of material lined up on both sides

of the track. However, peacocks abound and come very near to the hissing and

panting steam trains. They seem to be used to the sweet sounds the steam locos

make. Anyone can guess what will happen to them once the diesel brays out its

honk! There is acute water shortage after Dahinsara. So the train has to carry

both drinking water for the villages enroute and water to feed the engine at

Maliya Miyana. At Maliya the situation is even worse - the engine has to be

filled with buckets. It takes a good 5 people about 2 hours to satiate the YG's

thirst enough to get it back to Dahinsara.

At

Maliya the lazy Station Superintendent refuses to issue me a ticket back to

Morbi. He can't even figure out the permission letter from the railways that

I show to him. The ticket has to be bought on the train where a travelling ticket

clerk cum guard opens his ticket pandora's box and doles out tickets (all within

Rs. 5) to the entraining passengers. A Bengali family has travelled all the

way from Calcutta to see the eclipse. But to all our dismay the sky was overcast

heavily. A group of labourers from Andhra, working on the broad-gauge and bridges,

boarded and sat with me. The whole family works and travels together. Only one

man knows Hindi. He says he's been all over the country and picked up several

languages in the bargain.

Is

this the end...

Sadly so....

![]()